Divination and the Art of Choosing Well (Part II of II: Gamifying Hard Choices)

Divination without belief? On the practice of playing with prognostications.

This extended essay is the second of two parts, where I explore how divination may contribute to the art of choosing well. In the last part, I talked about divination as a practice of ingenuity and tenacity. In this piece, I’m exploring divination as play, or as gamification.

I’m publishing this much later than intended because, since last time, I’ve been back in the UK seeing family, and no sooner did we return to Taiwan when we moved house, down to the lovely city of Pingtung. What with arranging the move, scouring the second-hand furniture shops, and settling in, it’s taken longer than usual to get this newsletter out.

I’ll write more about Pingtung next time, but for now, let’s get started on these thoughts about why divination is worthwhile, even if you don’t believe in it, and how it can help you with choosing well, even if it doesn’t help you make better choices…

Happy reading, and—as ever—if you want to say hello, just drop me an email!

In the Mazu Temple…

The Mazu temple in Anping is one of the busiest in Taiwan’s southern city of Tainan. Particularly at weekends, the atmosphere is—as they say in Taiwanese Hokkien—lāu-jia̍t, or ‘hot and noisy.’ People bustle round the space of the temple, the air heavy with the fragrance of incense. Outside there are firecrackers, the raucous sound of music, street performers. And throughout the day and long into the evening, people come in and out to consult the goddess Mazu (or, in Taiwanese, Má-chó͘) about the big choices they face in their lives. They seek answers by throwing poe, or moon-blocks: red bamboo divination blocks, shaped like bananas cut in half lengthwise. Depending on how the poe fall, the answer is either that the goddess approves your question, or disapproves, or—more ambiguously—that she laughs.

You don’t need to spend long in Taiwan to realise that divination is everywhere. It is on the corner of the pedestrian street, where queues of students wait to consult a palmist whose advice has gone viral for its efficacy. It is on the TV, as well-dressed astrologers or Yijing (I Ching) diviners dish out help to people calling in from across the island. It is there in the hand-crafted Tarot cards sold in the craft markets that pop up in cities across the island nation every weekend.

In this very public enthusiasm for divination, Taiwanese culture may seem an outlier. But, in one form or another, divination is close to a human universal. As the Roman orator and philosopher Cicero claimed, there is no ‘people so civilised and educated, or so savage,’ as to fail to recognise the value of divination.1 Even today, this is still the case. Despite protests that divination is the sign of a culture turning its back on reason and Enlightenment values, divination still not only persists, but flourishes—and not only in Taiwan. Whether in Taipei or London, in almost every bookstore you can find a section dedicated to tarot, astrology or to the Yijing. Divination pervades popular culture. Under lockdown, divination has proliferated, from East Asia to the USA, and from the Middle East to South America. And since the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, this new cultural wave of interest in divination has shown no sign of letting up. Divination often flourishes in marginalised communities for whom the stakes are so much higher, for whom uncertainty is a fact of life. Tarot is booming among queer Indian communities. But divination is also found closer to the centres of power as well: in politics, and in the business world, as global companies consult Feng Shui geomancers, and as water companies in the UK resort to water diviners to find burst pipes.

But why does divination persist? In a previous piece, I wrote about divination as a way of making hard choices, as a practice of ingenuity and tenacity that may genuinely help us choose when our choices are not easy ones. Here, I want to go further, and suggest that it may be fruitful to think of divination as a kind of gamification of hard choices, one that helps not with making better choices, but with (and this is not the same thing) better choosing.

Asking the Gods

In Taiwan, perhaps the most popular form of divination is poa̍h-poe divination, or divination by poe divination block. In every temple, you can find sets of poe on the shrine for the public to use. You can also buy them on Shopee, Taiwan’s foremost online shopping platform, to use at home, which is what I did. Here are my poe:

To use the poe, first you introduce yourself to the god, giving your full name and address, as well as your date of birth, zodiac sign, and information about your family and your ancestors. I’ve been told that the gods—like many folks in Taiwan, and not without justification—are often perplexed by foreigners, so if you are not Taiwanese, you may have to go to greater pains to explain who you are and what your business is. As well as introducing yourself properly, you should ideally make some offerings of incense, snacks, fruit and sweet things. The gods are notorious for having sweet tooths. After this, you put your question to the god, and throw the blocks to see if the god assents to the question you are asking.

How the blocks fall indicates the god’s response. One block flat side down and one block flat side up (siūⁿ-poe 聖筶) indicates that the god is granting their assent. Both blocks flat side down (im-poe 陰筶) means the god is refusing to answer. And if both blocks fall curved side down, it means the god is laughing at you (chhiò-poe 笑筶). Usually, if you are doing things properly, three siūⁿ-poe judgements are required before your question is approved (the chance of approval, therefore, is roughly one in eight). However, some people when pressed for time just ask once, and go with that, hoping that the gods will understand that they have busy lives (the gods may protest that they too have busy lives, and look upon you less kindly: but sometimes compromises have to be made).

Next, you draw a numbered bamboo stick called a chhiam 籤 at random from a container by the altar, place the chhiam on the altar, and ask three times whether the stick is the right one. If it is not, you draw another, and the whole procedure repeats. Eventually, you have a chhiam the god is happy with.

Finally, to get your judgement, you go to a nearby cabinet, check the number written on the chhiam, and open a little drawer marked with the corresponding number. You take out a divinatory verse as an answer, written in Chinese characters in classical style.

This slip requires considerable amounts of interpretation: some busy temples will have an official, on hand to help you out and to make sense of the divination judgement you have received. For example, in the Anping Kaitai Mazu temple, there’s a small office where a friendly man in late middle-age—neatly dressed as if he has come to work in the tax office or some other bureaucratic organ of government—will invite you to sit down, and talk you through your question. In other temples, there may be a handy photocopied guide hanging nearby that you can consult.

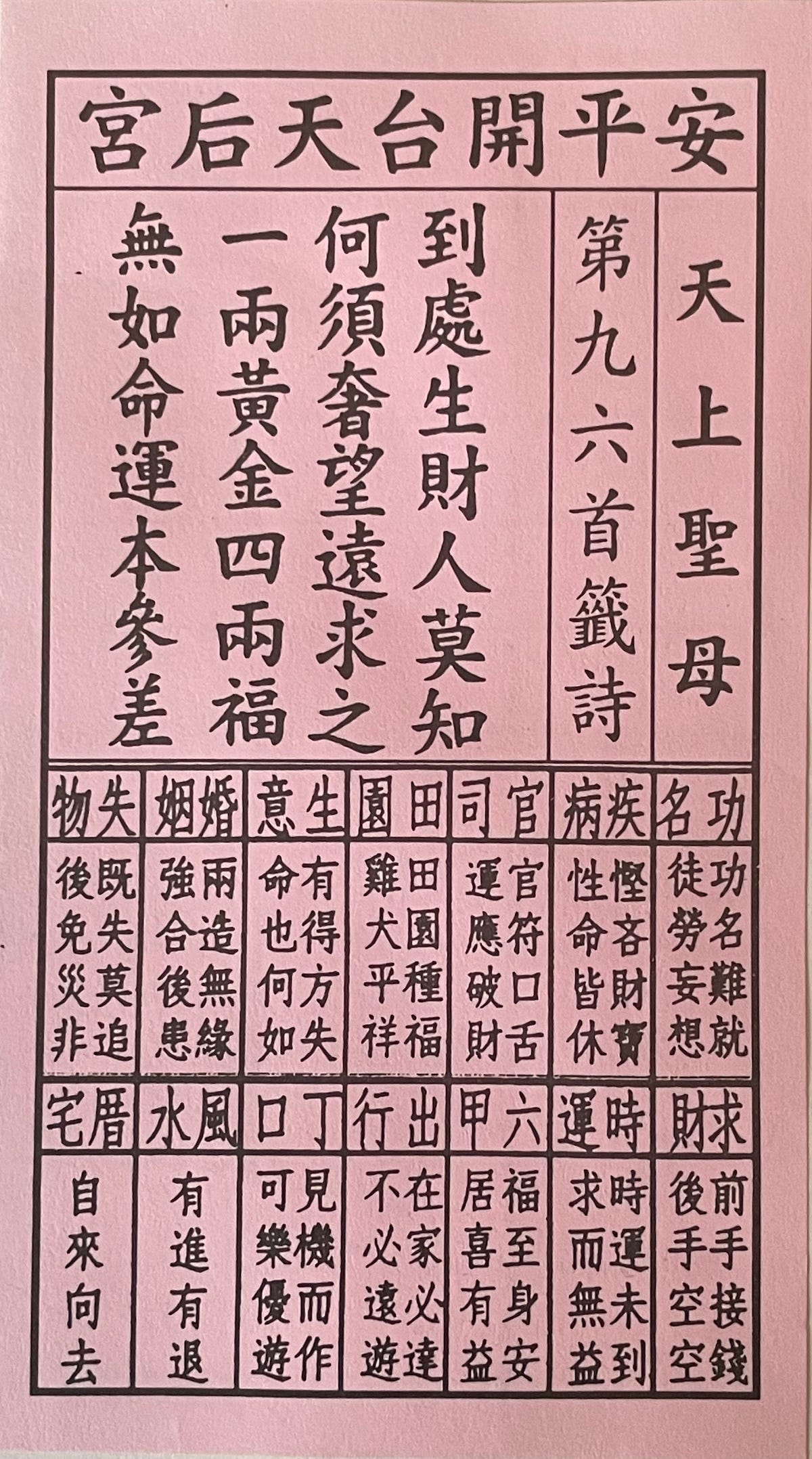

By way of example, here is a divination I received from the Anping Kaitai Mazu temple (安平開台天后宮). The top gives the name of the temple, while beneath is the number of the chhiam (in this case 47), and the verse. At the bottom, there are more specific judgements that reflect various matters, such as fame and success, sickness, official positions, agriculture, marriage and so on.

The obvious question here is why you would bother with all this. It takes up a lot of time. The gods are not always helpful. You can spend a lot of time getting the right question, and then when you receive your answer, it may be obscure and difficult to make sense of. Why would you take the trouble of dedicating a significant part of your day to engaging in such a long-winded and complicated procedure?

The answer is that, for many people, divination is useful. It helps with the difficult human business of choosing when our choices are hard. And this is why in Taiwan, for many people, big life decisions don’t just involve consulting friends and family-members, or deep reflection, but also consulting the gods (mn̄g-sîn 問神 in Taiwanese) to see what light they can throw on the question.

Gamified Decision-making

Since moving to Taiwan, when faced with hard choices of my own, I’ve also sometimes found myself heading to the temple to mn̄g-sîn, to check in with the gods, and to see what light they can throw on the matter at hand. And I, too, have found this a surprisingly useful practice. That is not to say I believe in the gods. I don’t. But acting as if I do seems a curiously helpful way of navigating some of life’s trickier choices.

If divination does not necessarily imply belief, this is because it can be understood as analogous, in certain important respects, to a game. This is an idea that I take, in part, from the anthropologist Stéphanie Homola, who argues that in divination, belief is beside the point. For Homola, what is crucial to playing a game well is not belief, but instead, a commitment, or willingness to accept the game’s rules of engagement. Or, if belief is at stake, the only thing one needs to believe is that here is a game worth playing. Here, I also think of my friend the Taiwanese writer Naomi Sím,2 who told me recently that consulting the gods by means of divination is a way of “gamifying” her life. It is a way of opening up creative and strategic possibilities, in the face of hard choices.

Homola writes as follows:

The game-like structure of divinatory procedures explains why many practicing persons feel evident discomfort when questioned as to whether they truly “believe.” This unease stems from an essential component of play, namely that adherence to its performative aspect should be considered in terms of “entering the game” and not of belief (Hamayon 2016, 192–99). According to Hamayon, the performative nature of play requires a personal commitment from the player, but one that is customary rather than spontaneous. In the case of divinatory practices, I would rather qualify such commitment as “procedural.” A client may approach a consultation with skepticism, but their commitment is no less absolute. It is the act of performing the technical procedure—either directly when throwing divination blocks or indirectly through a diviner—that triggers the commitment: one is either in the game or out, there is no middle ground.3

This idea that divination is a kind of play is one that also finds sanction in many traditions. Think, for example, of the deep connection between dicing, games and divination (when playing board games, do you ever blow on the dice to help influence your throw, as if your breath might summon a helpful god, or a gust of good luck?). Or think of the way that Tarot has its origins in a Milanese courtly parlour game. And in the Chinese tradition, the Xici Zhuan (繫辭傳), or the Commentary on the Appended Phrases of the Yijing (I Ching 易經), makes this connection clear, when it argues that divination is a way of playing with prognostications.

Thus, the one skilled in the arts of living abides and contemplates [the Yijing’s] images, and plays with its explanations; they act and contemplate [the Yijing’s] changes, and play with its prognostications.4

To play is not to commit oneself to believing, but to act on the basis that the game is worth playing, that entering into the game is a reasonable way to spend one’s time. As philosopher Ian Bogost writes in his book Play Anything, ‘That’s what it means to play. To take something—anything—on its own terms, to treat it as if its existence were reasonable.’5

This subjunctive as if is everywhere in play. We play on the chessboard as if we are commanding great armies at war. Children play shop—endlessly trying to persuade their parents to come and buy nonexistent objects—as if they had real goods to sell, as if they themselves were really shopkeepers.6 We play the board game Monopoly as if we are rapacious capitalists buying up the entirety of the city for our own personal gain, even if we are not. In this way, play takes place in this under the sway of this subjunctive as if.

What this means is that believing in Má-chó͘ (or in any of the other gods) is in no way a requisite for going to the temple to mn̄g-sîn. All you need to believe is that practising poa̍h-poe may be fruitful, efficacious, or otherwise worthwhile.

Seeing divination as a form of play allows us to throw some light on some other aspects of this almost universal human practice. Bogost argues that what marks out play from non-play is the fact that play takes place somewhere: on a board, or on a playground, a place where play happens within a certain prescribed structure.

Playgrounds, Bogost says, have two properties: boundaries or constraints, and contents. To enter a playground entails a constraint upon our freedom. In playing, we are not free to do anything we like, but we have to largely accept the constraints and boundaries that are a part of this playground. Why would we accept this limitation on our freedom? Bogost writes that ‘Play is a way of operating a constrained system in a gratifying way.’7 We play because these constraints ultimately give rise to abundance. Constraints make things more interesting.

In the context of Taiwanese divination, the temple is the playground. It is a bounded, constrained space. The constraints this playground offers are partly physical, they are partly set by the rules of the game of divination, and they are also, in part, established by the particular set of histories of that particular temple, the individual forms of practice that have grown up there. No two temples are quite the same, and the playground of divination in Taiwan is never a well manicured lawn, but is instead an uneven, lumpy territory. But this adds to the possibilities, and to the fun: as one gets to know the playing field (the particular temple) better, one can find more and more possibilities for forms of gratifying play—ways of giving rise to new forms of abundance.

As well as having boundaries or constraints, Bogost writes, playgrounds have contents, objects we manipulate or with which we play. These may be playing cards, dice, cricket bats, juggling balls, or—again in the context of Taiwanese temples—the poe, the chhiam, the incense, snacks and fruit that you offer. To play requires that we take these contents seriously. For example, if we were to play tennis with somebody who high-mindedly proclaimed there was no purpose in hitting a luridly fluorescent yellow-green ball back and forth over a piece of netting (from one point of view, not an unreasonable claim), this would close off the possibilities of gratification and abundance that tennis might afford us. Similarly, if we were to engage in divination without taking the playground and its constraints seriously, we would close ourselves off to the possibilities of gratification and abundance afforded by divination. Seeing the manipulation of the poe and the chhiam as foolhardy and ridiculous, that is to say, it to risk missing out on all kinds of fun. Both tennis and divination can certainly make the world more interesting, but only to the extent that as players, we take what we are doing seriously.

However, play is not just about manipulating things. As the philosopher Sarah Mattice writes in her book Metaphor and Metaphilosophy: Philosophy as Combat, Play, and Aesthetic Experience, play also involves playmates. Play is not just personal; it is interpersonal. Mattice writes that, ‘Play has a built-in place of priority for playmates—“I play” is already “I play with others.”’8 When playing tennis, our potential playmates include not only our opponents, but also the umpire, the spectators who have a stake in the game, our sponsors (if we are playing at a certain level), the gods to whom we utter prayers of thanks and curses, depending on how well the play is going, and many others.

What makes a playmate a playmate is that they are not just acted upon, but they also act on us in turn (the umpire’s decisions affect us, so do the cries and chants of the crowd). Play is mutual affectation, mutual transformation. Our playmates have a stake in the game, just as we do. In the context of temple divination, our potential playmates may include other temple-goers, attendants, interpreters, friends with whom take an afternoon off to mn̄g-sîn.

However, our playmates may also include other, more curious kinds of agents: the gods with whom we engage in conversation (or ‘as if’ conversation), even inanimate objects. And the reason for this is that, precisely because of the subjunctive as if nature of play, all contents are potential playmates, and the boundary between content and playmate is therefore porous. Maybe, as you practise divination, a sparrow lands on the altar just so, and as you ask yourself ‘what does this mean?’ In this moment, the bird becomes an active playmate in the game you are playing. Or maybe (as is commonly reported), as you throw the divination blocks, in the flickering half-light, you sense the smile on the face of the statue of the goddess Mazu change slightly.

Children know this porosity well. On entering the playground, a cuddly toy, a stick, a stone, a chair, a god…. in fact, anything can become a friend, an adversary, an ally, a thing with its own agency, in short—a playmate. What this also means is that inherent to play is a kind of animism, or at least the possibility of an animism. To one who is alive to the game, anything is potentially an agent, or can move from being simply content to being a more active playmate. Sticks can become friends. Statues of the gods—mere blocks of wood—can smile or speak.9

From Better Choices to Better Choosing

So, what are people in Taiwan doing when they go to the temple to poa̍h-poe? What am I doing when I do the same? Although people may have all kinds of beliefs about what they are doing and why, belief isn’t really the point of divination. The point is playing the game with the necessary commitment, treating it as if it were a reasonable thing to do. One enters into the playground that is the temple, and thereby finds that there open up certain possibilities for thought, action and play, precisely because this playground is constrained. One engages with the contents of the space, and with the playmates one fines (the other agents, or ‘as if’ agents, at work), to see what may in this whole process be fruitful, or productive, or—at the very least—interesting.

But, you may ask, how does behaviour—weird and irrational though it may seem—help us make better choices? And here is the interesting thing: if divination really comes into its own when we are faced by hard choices, then it doesn’t help us make better choices. Why not? Because hard choices, by definition, are choices where neither choice is necessarily better (or worse) than the other. However we approach the choice, the problem remains: there is no obviously better (or worse) choice.

If there were an obviously better or worse choice, things would be easy. We could resort to other less peculiar forms of reflection and practice to resolve things. For most of our everyday practical choices, often the best choice is so obviously apparent, we don’t agonise too much. Even when it comes to our moral choices, for a larger proportion of these, we already know what the best thing to do. If we hesitate, it’s more often than not because we find the best thing to do inconvenient—we’d rather not make the more moral choice, or we’d rather find a way of getting ourselves off the hook. It’s not, of course, that there aren’t great ethical dilemmas in our lives. It is just that most of our everyday ethical choices are not of this order, and dilemmas are relatively few. The problem, more often than not, isn’t knowing what the best thing to do is, it’s the follow-through. I think this is why, incidentally, Confucius claims, ‘Is goodness remote? I wish for goodness, and it is there!’10 Ethics, in the sense of knowing what to do, is really not that hard—at least most of the time.

In situations such as these, divination is not particularly useful. It is when faced by genuinely hard choices that divination comes into its own. And when we understand divination as play, we can see more clearly how it might be useful: not as a way of making our choices better (we can’t do that, precisely because the choices are hard, and ‘making our choices better’ makes no sense in this context), but as a way of making our choosing better.

In other words, divination can help us navigate hard choices, whatever we choose, in a way that is more satisfying, more interesting, more fun, more gratifying, more abundant. It allows us to inhabit our choosing more fully, to understand at last what it might mean to choose, and to give depth, shape and richness to our choosing, even when there is no best choice. And it allows us to be more alive to the adventure of a life we are constantly refashioning, without ever fully knowing what the future we are in the process of making will be.

Wardle, D. (2006). Cicero: On Divination, De Divinatione Book 1, Oxford University Press, p. 46.

I worked with Naomi on translating her brilliant Taiwanese language story about the goddess Má-chó͘, Emerald Orchid Love-Letter, one of the four stories in Tâigael: Stories from Taiwanese & Gaelic, the book I co-edited with Hannah Stevens. You should get a copy: as with all the stories in the book, Naomi’s tale of Taiwanese temple life is well worth reading (and you can listen to the story in Taiwanese, Mandarin, English and Gaelic here).

Homola, S. (2023). The Art of Fate Calculation: Practicing Divination in Taipei, Beijing, and Kaifeng (1st edition). Berghahn Books.

Ian Bogost, Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, The Uses of Boredom and the Secret of Games (Basic Books, 2016), p. 20

As children, my sister and I had a particularly vexatious game to which we subjected our parents. On walks by the river, we would stop at the paddling place where the water was shallow, and drag long skeins of weed and sludge out of the river, laying them on the nearby concrete bench. Then we would pretend (act ‘as if’) we were fishmongers, and compel our long-suffering parents to come and act as if they were buying our merchandise. The quantity of river weed being considerable, this game could extend for interminable lengths of time.

ibid. p. xi

Sarah Mattice, Metaphor and Metaphilosophy: Philosophy as Combat, Play, and Aesthetic Experience (Lexington Books, 2014), p. 65. Remember that this is all as if. We don’t need to make ontological claims about the existence of the gods to accept that they can be as if agents in the game!

This, incidentally, is why it came as no surprise to me when, late last year, I visited a temple in Taichung with a friend who is training to be a spirit medium, and he cast his eyes over the array of statues on the shrine, cocked his head to one side, and said, gesturing to the ranked gods on the shrine, ‘It’s pretty noisy here today. Everyone is at home, and they’ve all got something to say…’

Analects, 子曰:「仁遠乎哉?我欲仁,斯仁至矣。」Original on ctext.org. Translation my own.

Thanks for the article. I wanted to get your thoughts on a phenomena that I have observed in the dispositions towards astrology in India. Indian culture is big on astrology, and people here consult an astrologer (a "jyotish") for a wide range of decisions. From determining the most auspicious dates for a marriage, to knowing how long a planet's evil influence is going to impact your financial life, to how one should arrange the windows and rooms in the blueprint of a house.

Although these practices would not require independent justification in the past, I am increasingly aware of a sort of post hoc scientific rationalization for these divination practices. The people who engage in this do not seem to be satisfied by the heritage of the practice and seek to invoke (psuedo)scientific mechanisms and concepts to rationalize the practice.

My questions are the following:

1) Have you seen such a response from the people around you in Taiwan?

2) Why do people feel the need to do this? Are they insecure about the practice, and want to appear modern by legitimizing the practice using science? Maybe they feel attacked by the scientific worldview, and this is their defense?

3) Do you think people who engage in invoking these explanations lose out on something significant? That they won't be able to perform the activity of "entering the game" in its true spirit?